HPS Board member Paula Kalamaras has written a brief but detailed history of the Greek Gods. Read her interesting essay on “Mythological Origins” HERE

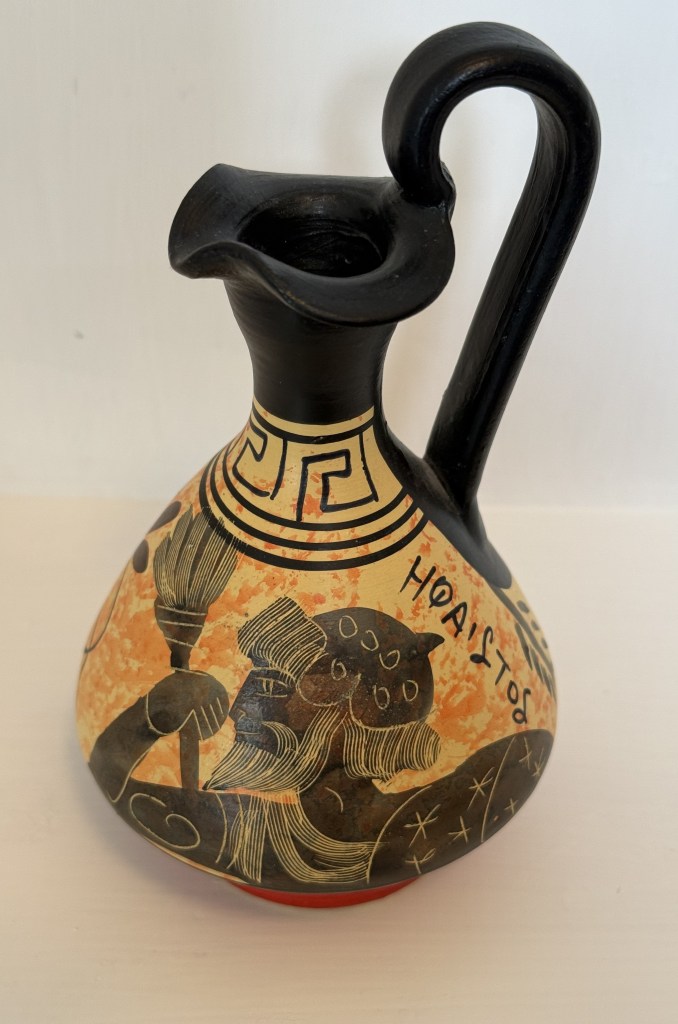

HPS President Dean Peters brought this treasure home from Rhodes last year. It portrays Hephaestus, the God of Fire and Forge. Show us your souvenirs of Greece here or on our FB page!

Ancient Greek Temples: Celestial Geometry and Astronomical Alignment

The placement of ancient Greek temples was far from accidental, according to the fascinating theory of geodetic triangulation. This concept suggests that the location of these sacred sites was intentionally designed to create precise geometric formations, reflecting a deep understanding of both earth and sky.

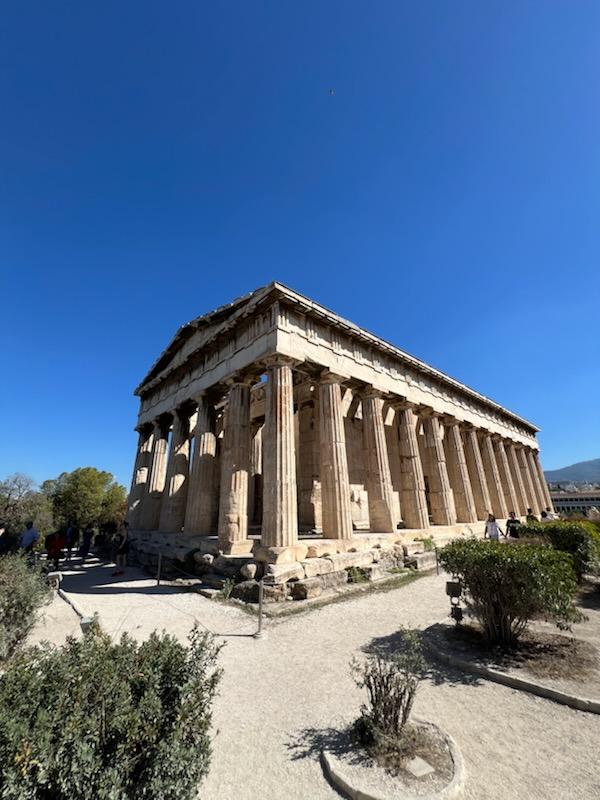

Across Greece, certain temples are aligned in ways that form distinct geometric shapes, such as equilateral and isosceles triangles. A notable example is the alignment of the Temple of Poseidon at Sounio, the Temple of Aphaia Athena on Aegina, and the Temple of Hephaestus in Thissio, near the Acropolis of Athens. Together, these sites form an isosceles triangle, an intentional pattern that seems too perfect to be coincidental. Similarly, another alignment involves the Temple of Apollo in Delphi, Aphaia in Aegina, and the Acropolis, creating a celestial connection across Greece’s most revered temples. Read more at Greek City Times

Greece promises “not to give up any rights” to Parthenon Sculptures

Government spokesperson Pavlos Marinakis on Wednesday discussed the meeting between Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and British Prime Minister Keir Starmer and a possible agreement regarding the Parthenon Sculptures. Read more from Greek City Times here

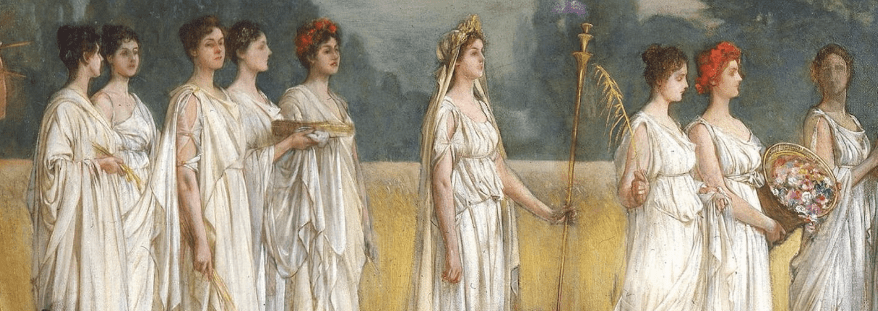

Did you know the Ancient Greeks celebrated a festival of Harvest and Thanksgiving in October and November? The Thesmophoria was a three-day, women-only event. Read more here at Greek City Times

HPS Welcomes Dr. Seth Pevnick, Curatorial Advisor, Greek and Roman Art Curator, Cleveland Museum of Art

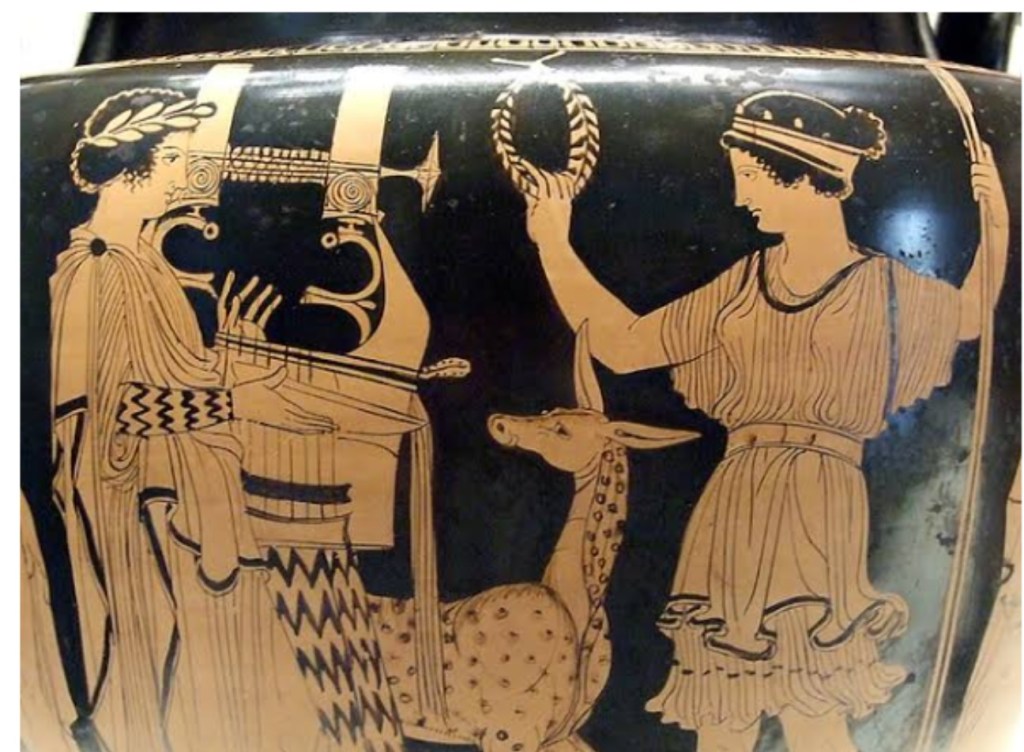

Dr. Pevnick has written extensively about the Cleveland Apollo, and his research can be seen here

His blog about a newly acquired Ancient Greek vase can be viewed here

Interested in more from Dr. Pevnick? Here are his articles about Athenian Potters and Painters and The Horse in Ancient Greek Art

The Cleveland Apollo

Tom Wendland, HPS Board Member

In the early 20th Century, Cleveland established its art museum. It was designed with a beautiful Neoclassical sensibility and built through a generous endowment from the city’s wealthy industrialists. For a city of its size and demography, the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) is a gem with an amazing collection. Though rarely mentioned in the same sentence as institutions like The Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, or The British Museum, CMA is home to a piece that is the envy of all of these. One could argue that the Cleveland Apollo is the most important piece of Classical Greek art known today. It is rare not only for being a bronze surviving from antiquity, but also for being the only original freestanding sculpture attributed to Praxiteles, the greatest and most renowned ancient Greek sculptor.

In antiquity the skill of Praxiteles was unmatched, and his influence spans the ages. Working mostly in marble, he was the first to sculpt the nude female form in life-size. He is credited with the invention of the S-curve, a common posture in lifelike sculptures. The influence of Praxiteles was so great that his sculptures were copied and copied again throughout the Roman imperial period. One of the more popular compositions was the Apollo Sauroktonos (lizard slayer). The Praxiteles original in bronze was mentioned by Roman author Pliny the Elder. It is now believed by many that this bronze Apollo is the very sculpture housed in the CMA.

When passing through the glass doors at CMA leading to Praxiteles’ Apollo, one is immediately struck by the beauty of the piece. Apollo leans against a now-missing tree, arrow in hand, prepared to stab a lizard. The hand and lizard are displayed in a case near the statue. The statue is dented mid-torso and the upper limbs are missing, but the composition is no less effective than it was when Pliny admired it two millennia ago. The inlaid eyes in the youthful face pop when set against the weathered bronze. It is a blessing for a museum to be able to feature an ancient Greek bronze, let alone one with such important history. In antiquity the vast majority of Greek bronzes were melted down to reclaim the metal, and extant Greek bronzes are the result of shipwrecks preventing the repurposing of the bronze (The Artemision Bronze), loss due to rock fall or other geological event (The Charioteer of Delphi), or other calamity during shipping (The Piraeus Athena). This adds to the mystery surrounding Cleveland’s Apollo. How did Praxiteles’s bronze Apollo, famous in antiquity, end up in a debris pile in an East German estate? The provenance between Pliny the Elder marveling at the piece of art and its arrival in post-reunification Germany is frustratingly blank. The estate’s owner, not recognizing the piece for what it was, sold it rather than invest in its restoration. It was then identified with correct dating and conserved properly. Eventually it was purchased by the CMA and received its deserved attention and study. This investigation is ongoing and will continue as this piece presents intriguing questions and answers about antiquity’s greatest artisan. However, being home to an incredibly important work of art with questionable provenance inevitably brings controversy.

In recent years, the art world has increasingly seen calls for the repatriation of important works of art. This is most famously exemplified by The Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum, which were either looted from the Parthenon by the greedy and duplicitous Lord Elgin or removed to the British Museum where they could be preserved and protected. Looking at the example of Lord Elgin, who was given the “right” to remove the Parthenon Marbles by Ottoman rulers (mere decades before Greek independence), represented an occupying and oppressive force in the region. However, it is also invaluable to society to have priceless works of art available for study and appreciation. When encountering the Apollo, most visitors pause for a moment and continue their trip, never realizing its colossal cultural value. Whatever the fate of the Cleveland Apollo, its importance and influence cannot be overstated.

The Olympians: Apollo

Paula Kalamaras, HPS Vice President

Who is Apollo and why did he battle the serpent Python?

Apollo was a god of many attributes and responsibilities. In fact, he is one of the few gods whose name was not changed when the Romans decided to adopt the Greek Pantheon and integrate it into their own. Even Zeus got a name change and became Jupiter. Apollo and his twin sister, Artemis (Diana), were born to Zeus and his mistress, the Titaness Leto. Hera, upset once again at her husband’s serial infidelity, punished Leto, since punishing Zeus wasn’t a possibility. Since Zeus was unassailable, Hera declared that Leto could not give birth on fixed land, so pretty much every place rejected the very pregnant goddess.

Ill-treated by Hera, Leto continued to wander the lands and islands on Gaia (the earth), unable to find a place. According to myth, Zeus finally intervened and had his and Hera’s brother (Poseidon) use his trident to strike the earth beneath the waters with his trident, and thus raise an island where Leto could give birth. This was the island of Delos, the smallest island of the Cyclades. Leto gave birth as soon as she landed on Delos – a small barren rock undetected by Hera. Artemis was born first – and because she was a goddess, pretty much full grown – and she aided her mother in delivering Apollo. Ever after, Artemis was both a virgin and the goddess of childbirth along with her half sister Illythia.

After the twins made their appearance, Zeus assigned them their aspects and attributes. Leto remained on Delos, which became holy not just to her but her twins as well, and temples to all sprang up there. Artemis became the goddess of hunt and wild animals, as well as childbirth, and represented the moon (along with Selene). Apollo had a more eclectic set of attributes – he was the god of poetry, light, oracles, music and more.

However, Apollo was an ambitious young god and wanted a home for his oracles. He set his sights on Delphi. The only issue with Delphi as a site for his oracle was that there was an oracle in residence already – the serpent Python. Apollo decided to battle the serpent, not just for his oracle site, but because Python had neglected to help Leto as she sought a birthing place. This also upset her children, and Apollo took it upon himself to defeat Python. Once the snake was slain, the young god laid claim to Delphi, but in an acknowledgment of the original oracle, Apollo’s oracle – always a woman – was called Pythia. For many centuries kings, philosophers, men, women and many others made their way to Delphi, where Apollo’s oracle gave her pronouncements and interpreted the message of the god.

HPS has recently formed a committee to explore the links between the Ancient and Contemporary effects that Greece has had on NEO. Chaired by Board Members Paula Kalamaras and Tom Wendland, this committee will provide presentations and education both virtually and in person. Stay tuned for updates, and like us on Facebook for more information.

Photos from the tomb of St. Demetrios, Thessaloniki